A towel, it says, is about the most massively useful thing an interstellar hitchhiker can have. Partly it has great practical value. You can wrap it around you for warmth as you bound across the cold moons of Jaglan Beta; you can lie on it on the brilliant marble-sanded beaches of Santraginus V, inhaling the heady sea vapors; you can sleep under it beneath the stars which shine to redly on the desert world of Kakrafood; use it to sail a miniraft down the slow heavy River Moth; wet it for use in hand-to-hand combat; wrap it round your head to ward off noxious fumes or avoid the gaze of the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal (a mind-bogglingly stupid animal, it assumes that if you can’t see it, it can’t see you – daft as a brush, but very very ravenous); you can wave your towel in emergencies as a distress signal, and of course dry yourself off with it if it seems to be clean enough.

More importantly, a towel has immense psychological value. For some reason, if a strag (strag: nonhitchhiker) discovers that a hitchhiker has his towel with him, he will automatically assume that he is also in possession of a toothbrush, washcloth, soap, tin of biscuits, flask, compass, map, ball of string, gnat spray, wet-weather gear, space suit, etc., etc. Furthermore, the strag will then happily lend the hitchhiker any of these or a dozen other items that the hitchhiker might accidentally have “lost.” What the strag will think is that any man who can hitch the length and breadth of the Galaxy, rough it, slum it, struggle against terrible odds, win through and still know where his towel is, is clearly a man to be reckoned with.

Coding Color

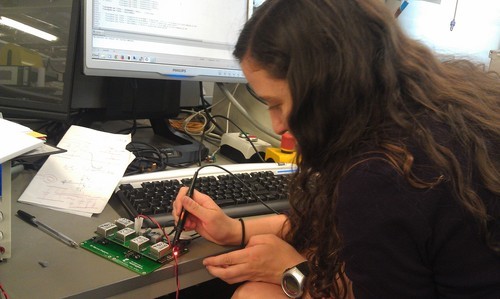

One afternoon, Dimi and I decided to mess with some red, green, and blue LEDs. The three lights were on a chip which was located in the corner of one of those forest green circuit boards you see when you take apart an old DVD player or computer. So the lights were stuck there on the board; they received a voltage and a current that we could not easily change and therefore we had no control over how brightly each LED shone. But we could turn each LED on and off really quickly, like a strobe light in a haunted house, or blinking multicolored Christmas lights, but faster. I wanted to make my favorite color, purple. But how to make purple light with red, green, and blue? First, a bit of Color 101.

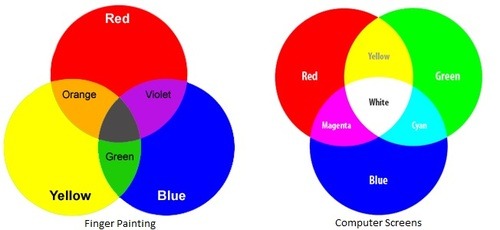

The lights in our TV’s, projectors, computer screens, and LED’s don’t follow the same color system as the one you learned in grade school art class.When kids play with finger painting, they learn that there are three primary colors: red, blue, and yellow. Any combination of those three can produce whatever color you can imagine. If the messy kid next to you decides to go HAM and mix all of the colors, suddenly they are left with brown or black.

But, if you’re working with light, it’s the complete opposite: mix all of the colors together and – as anyone who’s ever played with a kaleidoscope or prism or seen Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album cover, you know this one – you get white.

With light, the primary colors we use are red, green, and blue – this is why whenever you turn on a projector that funky screen appears with RGB at the bottom. (Random sidenote: RGB is also my initials and I truly believed the CIA was trying to send me messages through the projector – but you know it’s cool it’s this color thing too). Fancy color people call the finger painting system ‘subtractive’ and the light system ‘additive’ when they describe the two color systems, as seen side-by-side in the images below.

Like an impressionist painting, millions of these tiny red, green, and blue dots combine on your computer screen to allow you to read these words or watch your favorite movie. (You may even be able to take a magnifying glass to your screen and see it yourself).

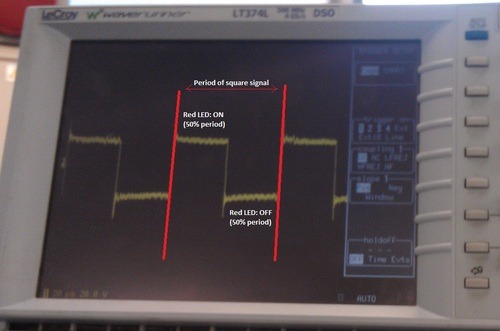

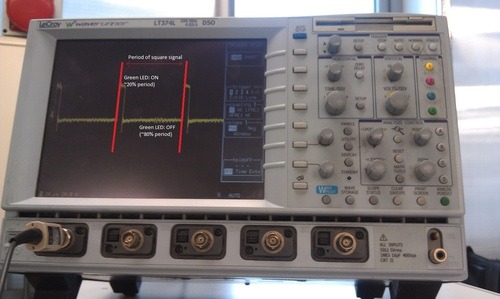

Back to Dimi’s and my experiment with purple light. We knew combining red and blue make purple. And, since we couldn’t control the brightness or where the LED’s shone their light, we decided to control how long each light was turned on. By quickly switching between the red light being on and the blue light being on, the average could become purple. We did this by sending a square signal to tell the switch when to turn on and off, as seen in the picture below.

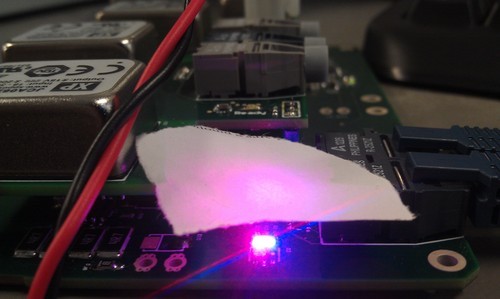

This is the square signal turning the red LED on and off. The time in between the two red lines represent the period of the square signal – the pattern within the two red lines will repeat over and over again until we tell it to do something else. So if we want red and blue to be on an equal amount of time, we tell the red light to stay on for half of the period time and then turn off for the other half of the period time. The period time can be really small – on the order of microseconds – which means your eye sees the two lights rapidly flickering. When we implemented this and looked at the LED’s directly, they were too bright and you could still see two individual lights – and that wouldn’t work. So we put a piece of paper over the two separate lights to act like a filter/surface for the lights to converge onto, and behold! Purple!

But what about orange? In our new RGB system, orange is a combination of red and green. But this time, we needed to combine different levels of red and green light. When we made purple before, we could turn the red light on for half of the time and then turn the blue light on for the other half of the time. But for orange, we needed approximately 80% of the light to be red and 20% to be green – so we told the switches to spend more time keeping the red light on and less time keeping the green light on. (This makes our square signal look more like a rectangle, but for some reason we still call it a square signal.) The signal shown below shows the green LED: the period in between the two red lines shows the green LED is on for a small percentage of the period and off for the rest of it. The signal for the red LED would be exactly the opposite.

The piece of paper helps to combine the two lights and shows orange on its surface (the picture turned out more yellow, but you get the point.)

Changing that square signal allows us to change what color light we see, right? Congratulations, you now understand Pulse Width Modulation (PWM). In electronics, instead of controlling what shade of color we see on a piece of paper, we use PWM to control other things like voltage. Instead of a piece of paper, we use inductors and capacitors to average things out. Our lightswitch turning each LED on and off is called a transistor. PWM is simply a square signal that turns the transistor on and off – like your finger turning on and off a light switch. Instead of your brain controlling your finger, we use programming to control what the square signal looks like. The square wave is a voltage wave, and thus we can look at the image on an oscilloscope (the fancy machine with all the knobs that showed us the square signals earlier).

In truth, color has nothing to do with my research this summer. Dimi and I were just messing around with some indicator lights one afternoon. But Pulse Width Modulation does. My work this summer surrounded building a converter: a device that converts the three-phase alternating current a motor produces to the direct current our laptops and cell phones consume. We use PWM to help accomplish this. See future posts for more on converters!

An afternoon in Basel, Switzerland

Nottwil, Switzerland

Murderball

Old friends in new places

July 11-13, 2014

Nottwil, Switzerland

One of my best friends, Eric, is a quad rugby athlete. If you have never heard of quad rugby, I feel sorry for you. It’s like demolition derby in wheelchairs – except with actual rules and a volleyball. It can also be called wheelchair rugby or murderball (a documentary of the same name is a great introduction into the player’s world). In high school, whenever Eric’s team, the East Coast Cripplers had an odd number of players, I loved to jump into one of the shiny metal-plated wheelchairs and ram into people. Eric now represents the United States as part of Team Force, a sort of farm team for Team USA who go to the quad rugby World Championship every year and the Paralympics every four years.

In quad rugby, each player is assigned a number based on the extent of his or her disability. To keep teams relatively even only four players with a total value of no more than 10 points can be on the court at any time; this forces teams to play a combination of less functional “low pointers” and more capable “high pointers.” Players can span from double amputees still able to walk (which seems a little dubious in a wheelchair sport) to players with much more severe spinal cord injuries; and criteria for assigning you a point value can range from how well you can manipulate your fingers, turn your head, or wield your trunk to reach for a ball. The main point of the game, as in most sports involving balls, is to get your ball into the other team’s goal. After that, there are lots of little rules. You have to dribble the ball every ten seconds. You have a certain amount of time to get the ball at half court and then you have a certain amount of time to score. You can only have three chairs in the goal box defending, not all four. Like soccer you can have overturns and fouls and out of bounds. And like basketball, games can either be really boring with players just constantly rolling back and forth across the court or nail-bitingly intense with fast maneuvers, head-on collisions, and gutsy plays.

For a year or so now, Eric has been living with his fiance Andrea in Houston, Texas and I of course have been all over the place/in the middle of nowhere (also known as Blackburg, Virginia) – and thus it’s been awhile since I’ve been able to see him. So imagine my delight when I learned he had a tournament with Team Force in Switzerland while I am here across the pond! (Sad that it’s easier and cheaper to take a long weekend in Switzerland from England than go from Virginia to Texas). So Thursday morning, I boarded a bus from campus, got on a train in Nottingham, switched trains at Leicester, checked in at Stansted airport, flew to Basel, Switzerland, took a bus to the train station, ran onto a train bound for Sursee, couldn’t understand German and boarded the wrong train to Luzerne, and finally got on the correct train that happily dropped me off at Nottwil. Precisely where Eric and Kevin were about to board the same train to go looking for me. Instead, we walked through the rain to the hotel and tried to not squish slugs.

I soon learned why this seemingly random place had been chosen to host this international tournament. It seemed to be a hospital/rehabilitation center/conference center/hotel/sports center devoted to paraplegics. Ramps and wide paved sidewalks lead you around the facility, to the edge of the lake, and through gardens. Eric’s hotel, a tall modern-style cement structure that went up four or five floors and underground at least two, had automatic everything. The combination drab concrete and automation made me feel like I was in the futuristic dystopia of the Hunger Games or Divergent. Tall doors giants could fit through opened automatically as you approached. Clear glass doors that has just looked like window dividers opened automatically as you walked past. The doors to each room sat at 45 degree angles to the walkway, creating a zigzag effect in the walls. As you entered each part of the hotel room itself – hallway, bathroom, main room, etc – lights would automatically turn on. But all of the outlets and tv would not work until a room card was placed in a slot near the entryway. Instead of wasting energy by leaving things plugged in all day or stressing trying-to-be-environmentalists out with unplugging things and surge protectors, this hotel allowed you to shut your entire room down with a chip in a plastic card. Of course this was slightly annoying if you did need to charge things (like my cell phone, camera, laptop) while you were away. (There’s no winning, is there?)

While Eric and Kevin (another former East Coast Crippler) went to team meetings, I wandered around Nottwil. A path with a diamond shaped label that said “wanderweg” followed in between the railroad tracks and tall grasses abutting the lake’s edge. It varied between gravel and pavement but seemed to go on steadily next to the rail for miles. Smaller side trails lead you to the peaceful edge of the lake. Ramps lead me back under the railroad tracks onto smaller roads with houses poking out of every corner. I followed a sign that advertised for camping and instead found a field full of wildflowers and a tidy neighborhood filled with campers that looked like they hadn’t been moved in years. (If that was a trailer park, it was the most beautiful, cared-for one I have ever seen). Larger homes stood like tall barns over wide fields, keeping watch over a herd of cows and supporting mountains of chopped wood stacked against the wall. A newer (probably Catholic?) church stood at the top of the landscape and proudly rang out the time to the town below (the Swiss are very precise in their time – Rolex proudly sponsored all the analog train station clocks – and when I had gotten on the wrong train earlier, the ticket man scolded me that obviously I had wanted the 5:34 train (that left from that exact same platform) so why had I gotten on the 5:28? (You’re serious, right?)). Stores in the town seemed to open and close whenever they pleased. I saw a bride and groom’s bachelor and bachelorette party occur on opposite ends of the same bar as it was probably the only one open in town. The bar itself was painted every bright color a thirteen year old girl would choose for her room in the hopes it might become a slumber party mecca and the decorations had an americana-beach-boys theme – all of which contrasted oddly with the gray clouds and rain that permeated the sleepy atmosphere of the Swiss town.

But I always made sure to return from these excursions in time to make Team Force’s next game. USA seemed to have a lot going for them: Eric had made the brilliant trip hashtag #ForcingSwitzerland that seemed to be catching on (It was hilarious, but also couldn’t be objected to by higher-ups because it was true), they were the best of the best from various club teams across the country, and I was here as their cheerleader. Alas, the team was new and still learning how to effectively work together; they improved vastly each game they played and worked incredibly hard but could never find the elusive win the whole weekend.

I learned a lot about how different the rest of the world can be. Eric and his teammates earn $250 a month for being professional US athletes. Which maybe if you were to save that over the course of a year would be enough to buy you the special rugby chair needed to even play the sport. Eric pays his own way to every tournament. For Switzerland he started a crowd-funding campaign to offset the thousands of dollars just the flight would cost him. Great Britain’s team, meanwhile, is on the opposite end of the spectrum. They are paid a yearly salary just for being on the team (I heard lots of numbers being tossed around, so I don’t want to report inaccurately but it’s probably in the range of 30,000 pounds). Their sweatshirts, t-shirts, flights, hotels – all the little things that add up quickly – are paid for. Just being on this team and playing rugby could be their entire profession. The rest of the world is somewhere in between the two extremes of the USA and Great Britain. And yet, USA has medaled in the Paralympics every year since their introduction.

I also learned a lot about Switzerland. Everyone knows an absurd amount of languages. Swiss itself is only a spoken language, not written. And even then different dialects are spoken in different parts of the country. Street signs are thus often in German. So people know Swiss, German, French or Italian (or both) depending on which country is closer, and very often English. Almost everyone I spoke with knew conversational English. And an English speaking country doesn’t even border them. Which makes every citizen fluent in two to three languages and conversational in three to five. Which blows my mind. The Swiss have also taken the precautionary principle to heart. Clean water is considered a basic human right – and public fountains are scattered everywhere to provide free access to some of the best water I have ever tasted. When people see trash on the street, they go over and pick it up. And probably recycle it. Every citizen is required to serve two years in the military. And when their service is up, they take the weapon they were issued home with them and store it in their bunker. Because every building is required by Swiss law to have a nuclear fallout shelter. Instead of a normal basement, most homes apparently have reinforced steel and some sort of ventilation system along with it. Eric’s hotel room had two entire underground floors seemingly just for this purpose. Even much of the military is apparently housed underground. Though Switzerland is committed to neutrality, they seem to be the most prepared in the world to quickly burn their bridges (literally), defend their land, and keep their citizens safe should a real apocalyptic scenario occur. What a completely different way of life (though obviously it has allowed the world to trust in its banking, the quality of its products, and helped the country get through WWII).

And, of course, as Eric, Kevin and I browsed the channels on the hotel room’s tv, the only two English speaking channels were BBC and MTV. We settled on MTV for a bit and watched a show on women who work at a Hooters-like restaurant in Texas where all they seem to do is sell alcohol and get in petty fights with each other. It was not the best image America could really broadcast to the world. And in contrast to all the dutiful things Switzerland seemed to be doing, really made you wonder why more global perspectives aren’t normally a part of the national conversation.