London to Paris in 2.2 hours

A weekend with Cassie

Coding Color

One afternoon, Dimi and I decided to mess with some red, green, and blue LEDs. The three lights were on a chip which was located in the corner of one of those forest green circuit boards you see when you take apart an old DVD player or computer. So the lights were stuck there on the board; they received a voltage and a current that we could not easily change and therefore we had no control over how brightly each LED shone. But we could turn each LED on and off really quickly, like a strobe light in a haunted house, or blinking multicolored Christmas lights, but faster. I wanted to make my favorite color, purple. But how to make purple light with red, green, and blue? First, a bit of Color 101.

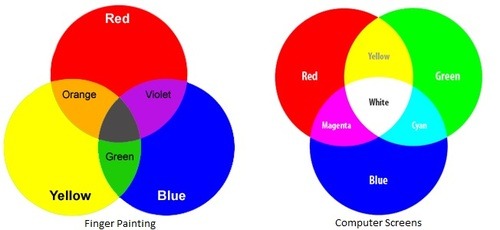

The lights in our TV’s, projectors, computer screens, and LED’s don’t follow the same color system as the one you learned in grade school art class.When kids play with finger painting, they learn that there are three primary colors: red, blue, and yellow. Any combination of those three can produce whatever color you can imagine. If the messy kid next to you decides to go HAM and mix all of the colors, suddenly they are left with brown or black.

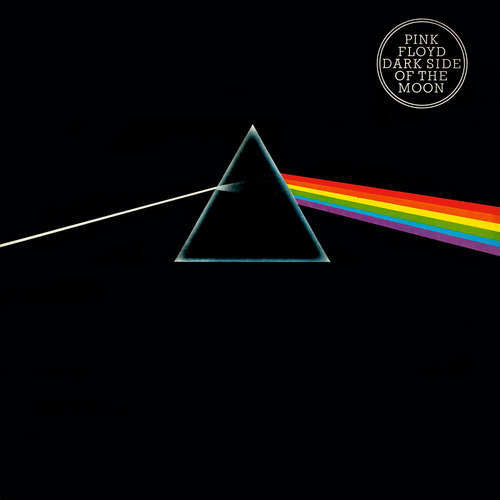

But, if you’re working with light, it’s the complete opposite: mix all of the colors together and – as anyone who’s ever played with a kaleidoscope or prism or seen Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album cover, you know this one – you get white.

With light, the primary colors we use are red, green, and blue – this is why whenever you turn on a projector that funky screen appears with RGB at the bottom. (Random sidenote: RGB is also my initials and I truly believed the CIA was trying to send me messages through the projector – but you know it’s cool it’s this color thing too). Fancy color people call the finger painting system ‘subtractive’ and the light system ‘additive’ when they describe the two color systems, as seen side-by-side in the images below.

Like an impressionist painting, millions of these tiny red, green, and blue dots combine on your computer screen to allow you to read these words or watch your favorite movie. (You may even be able to take a magnifying glass to your screen and see it yourself).

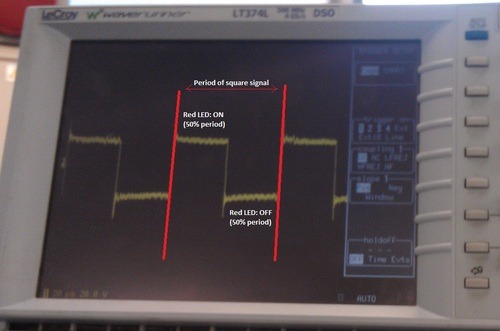

Back to Dimi’s and my experiment with purple light. We knew combining red and blue make purple. And, since we couldn’t control the brightness or where the LED’s shone their light, we decided to control how long each light was turned on. By quickly switching between the red light being on and the blue light being on, the average could become purple. We did this by sending a square signal to tell the switch when to turn on and off, as seen in the picture below.

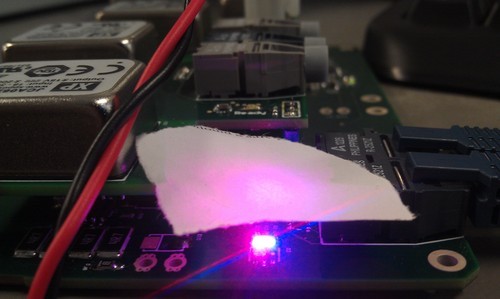

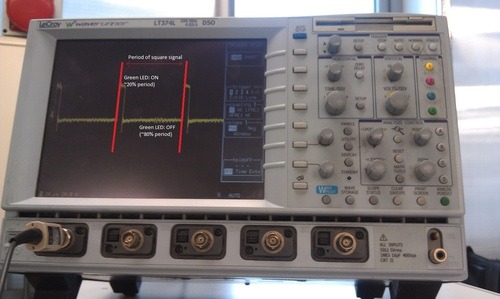

This is the square signal turning the red LED on and off. The time in between the two red lines represent the period of the square signal – the pattern within the two red lines will repeat over and over again until we tell it to do something else. So if we want red and blue to be on an equal amount of time, we tell the red light to stay on for half of the period time and then turn off for the other half of the period time. The period time can be really small – on the order of microseconds – which means your eye sees the two lights rapidly flickering. When we implemented this and looked at the LED’s directly, they were too bright and you could still see two individual lights – and that wouldn’t work. So we put a piece of paper over the two separate lights to act like a filter/surface for the lights to converge onto, and behold! Purple!

But what about orange? In our new RGB system, orange is a combination of red and green. But this time, we needed to combine different levels of red and green light. When we made purple before, we could turn the red light on for half of the time and then turn the blue light on for the other half of the time. But for orange, we needed approximately 80% of the light to be red and 20% to be green – so we told the switches to spend more time keeping the red light on and less time keeping the green light on. (This makes our square signal look more like a rectangle, but for some reason we still call it a square signal.) The signal shown below shows the green LED: the period in between the two red lines shows the green LED is on for a small percentage of the period and off for the rest of it. The signal for the red LED would be exactly the opposite.

The piece of paper helps to combine the two lights and shows orange on its surface (the picture turned out more yellow, but you get the point.)

Changing that square signal allows us to change what color light we see, right? Congratulations, you now understand Pulse Width Modulation (PWM). In electronics, instead of controlling what shade of color we see on a piece of paper, we use PWM to control other things like voltage. Instead of a piece of paper, we use inductors and capacitors to average things out. Our lightswitch turning each LED on and off is called a transistor. PWM is simply a square signal that turns the transistor on and off – like your finger turning on and off a light switch. Instead of your brain controlling your finger, we use programming to control what the square signal looks like. The square wave is a voltage wave, and thus we can look at the image on an oscilloscope (the fancy machine with all the knobs that showed us the square signals earlier).

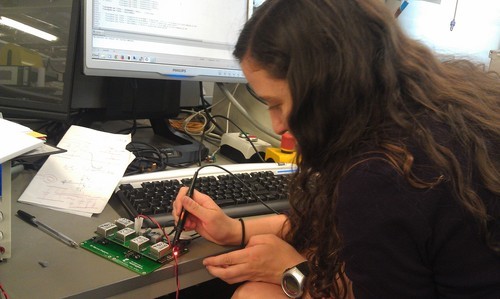

In truth, color has nothing to do with my research this summer. Dimi and I were just messing around with some indicator lights one afternoon. But Pulse Width Modulation does. My work this summer surrounded building a converter: a device that converts the three-phase alternating current a motor produces to the direct current our laptops and cell phones consume. We use PWM to help accomplish this. See future posts for more on converters!

Pitcher and Piano

Dark Knight Rises into taxidermy hell

Nottingham lace district

Nottingham Castle

June 28, 2014

Today was explore Nottingham day.

Downtown Nottingham is two and a half miles East of our comparably deserted summer campus. Two and a half miles doesn’t seem like very much, especially when I used to run 3.1 miles in twenty or so minutes, but out-of-shape-walking-uphill-and-slightly-lost is apparently a very different experience. We now take the 1-pound bus. Nevertheless, I was elated to find a small road along our journey had been named after Faraday (woo! Science!):

We reached the castle at 11am. Wedding guests for the third wedding we had seen that Saturday morning were beginning to file through the castle gates and into some unknown courtyard. The grounds were well manicured, with delightful Robinhood references sprinkled throughout, the top five finalists of a children’s contest to create the new Nottingham Castle flag waved over a field of screaming children attempting to tackle their father.

I began to read signs.

On top of the first hill I learned that the civil war started on my birthday (obviously my birth is the more important of the two):

“Near this site King Charles I raised his royal standard on August 22nd, 1642 an act which marked the beginning of the English civil war”

At an outer entrance into the castle I learned the castle wasn’t a castle:

“The medieval castle was almost completely demolished in 1651 at the end of the Civil War to prevent it being used again as a military stronghold.

After the Restoration of King Charles II the site was bought in 1663 by William Cavendish. He had been made first Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne for his support of the Royalist cause in the Civil War. He cleared away many of the remains of the medieval castle so that, in 1674, he could build a magnificent mansion, the shell of the present building.

In 1831 the local people were angered by the fourth Duke of Newcastle’s opposition to the Reform Act that would have given them wider voting rights. They rioted and set fire to the mansion. The statue of the first Duke on horseback that you can see above the door was smashed by the rioters. Although the Duke received 21,000 pounds in compensation, he left the burnt out shell as a silent rebuke to the people of Nottingham.”

Wow. What a mosaic of history. And string of jerks. Later on I learned the Castle had been ordered to be built by William the Conqueror in 1067. 1067. That means over the past 900 years this piece of land has gone from pretty hill to strategic fortress to mansion to a symbol of exorbitant wealth and oppressive government. How hard is that to conceive? My Irish Starbucks barista made the greatest comment the other morning: “In England 100 miles is far; in America 100 years is old.” The “magnificent mansion” and damaged statue of the first duke can be seen below:

The Castle also had a pretty cool view of all of Nottingham. Channel your inner William the Conqueror, rich Cavendish, or angry rioter as you look out over all that is yours. Like the University of Nottingham in the very far back right. Or the coal power plant in the back left.

Inside the castle, we moved slowly through a maze of rooms. Just when you thought you had seen everything, another room or staircase would appear with another themed exhibition.

We started with a grade-school-on-field-trip room that urged you to organize their random collection of artifacts into categories of organic, ceramic, and metal materials;

then a gallery on the local military regiment through the modern era;

then some early 20th century paintings, followed by a room of abstract modern art;

then a coffee shop;

then a children’s play area with costumes and felt paintings and a castle;

then rooms filled with porcelain and glass;

then a gift shop;

then an augmented reality display on the 1831 riots;

then a children’s room made to look like Sherwood forest where you can dress up as Robinhood.

And I think that was it? Who knows what rooms we may have left uncovered. At some point Jill and I somehow got separated from Missie and Ryan. So Jill and I took it slowly. We read plaques comparing the painting styles of a husband and wife; we stared at the modern art looking for meaning within dashes and teddy bears; but mostly we played in the Children’s areas. I donned a Sherlock hat and posed. Jill vogued it up in a Robinhood cape. When we began playing with a felt board with an idyllic pastoral scene, I scolded Jill for trying to put the felt cows near the felt river so they could drink felt water. Instead, I grabbed some felt shrubbery to make a felt riparian buffer to protect the felt stream from the evil felt cows which I placed in a field on the other side of the felt painting. Crisis averted guys. I totally restored that felt water quality.

My inner IB history nerd was in love with the exhibit for the 1831 riots. Unlike the earlier exhibits that had urged a superficial analysis of artifacts or simple costume play for grade-school ages, this exhibit’s walls asked questions like “Who writes history?” “Whose views are important enough to be heard and recorded?” “What would you have done in 1831?” The riots occurred during the shaky decades of transition between monarchy and democracy when leaders tried desperately to hold on to what remained of their power and the country tried to determine exactly what age, status, wealth, sex, or race could allow you to vote (though obviously non-white people and women would have to wait another 100 years). The exhibit presented primary sources of newspapers from the day, quotes from all sides of the issue in white scribbles of paint against the black wall, and a blackboard for you to leave your own white scribbles of thoughts in chalk. The augmented reality displays – an interactive I-Pad hanging from the ceiling whose camera recognized where you were pointing – would bring lifeless paintings and models to life.

At 2pm, Maid Marion arrived in the atrium to lead 30 of us on a Nottingham Castle cave tour. She was brilliant – immediately memorizing every child’s name and their doll’s name – and ably juggling giving all the adults a short history lesson while corralling all the children with ghost stories, pigeon nests, and that motherly-you-better-behave glance. The castle-mansion-thing stands atop a hill made of incredibly soft sandstone that through the ages people have carved dozens of tunnels through. They served as a method of quick escape for some and an unknowing downfall for others. Maid Marion amazed the kids when she pointed out the line of Jurassic-era rock in the walls and told them they could be touching dinosaur sand and rocks. I touched the wall too for good measure.