Before I can talk about the Inka Trail hike in Peru, I have to back up and discuss how I almost killed Mike in the Grand Canyon. For Mike’s graduation trip, I had researched this super famous trail from the rim of the Grand Canyon down to the Colorado river – it was well supported with camping sites, water sources, and even a restaurant at the bottom. Online, middle-aged, overweight men gave the trail five stars, beaming that “if they can do it, anyone can!” Mike had never set up a tent before and never been multi-day hiking. But I knew what I was doing (right?), I had the water filters and sleeping bags and tents, and this trail seemed so worn, it could be an epic, safe first hike for Mike.

We got there and the nice, known, amenity-filled, famous trail was booked. Every campground and trail permit in the national park was booked. The lady behind the counter instead sent us into the “wilderness”, the unregulated public land outside of the national park. At the Colorado river, we could hike back into the national park and stay at a real campground the second night. Seemed reasonable – and she reassured us that two other couples would be on the trail with us. At the last second, almost as an afterthought, we bought the topographic map to make sure we could follow the right trail. At $15 the map cost twice as much as our three day, two night hiking/camping permit – it felt like an extravagance.

But it turns out wilderness is actually wilderness. There can be no structures like signs, trail markers, water sources, and campgrounds. Other hikers had stacked rocks into guiding sculptures to point the way. This worked well until we came upon a landslide and got lost for two hours trying to discern the human-stacked rocks from the rock-slide pile of rocks. We didn’t run into a single other human the first day. Or find any water. We pitched our tent on a flat plane with sweeping, gorgeous views of the canyon. But the desert is eerily silent at night and I tossed and turned hoping the small stream below our perch on the map could give us water the next day. It felt like our lives depended on the suddenly not-so-extravagant purchase being correct.

We did find water the next day – but the entire hike had been way more strenuous than we expected: the first day was entirely walking down stairs which hurt Mike’s knees, the second walking beside the Colorado river (water! flat plane!) entirely exposed to the harsh sunlight, and the third day was an entire day of climbing “the cathedral staircase” which hurt my lungs. The exhaustion and worry almost outweighed the sweeping views, joy of finding a hidden, watery oasis, and sense of accomplishment in conquering the trail.

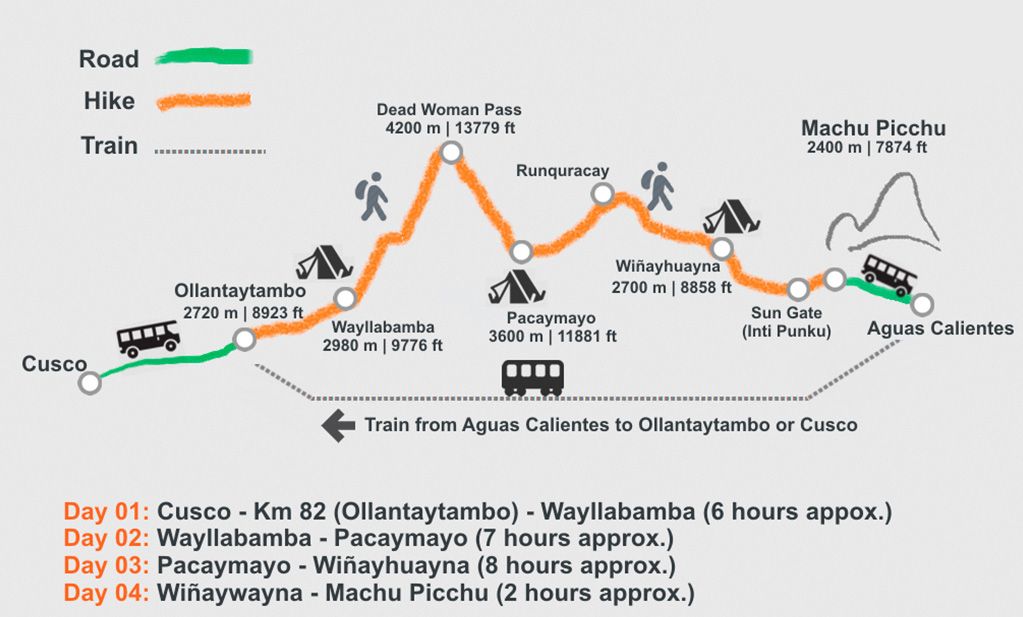

So this time was going to be better. We reserved spots in a guided hike along the Inka Trail to Machu Picchu in Peru. There was no getting lost, no being without water, and no sense of isolation. Porters carried all the food, cookware, and tents so all we had to carry was a sleeping bag and change of clothes. Professional chefs cooked every meal. Guides waited for us, advised us, and showed us where all the best views were – no planning required. All kinds of people have done this trail for hundreds of years! It will be a breeze.

But it was still a trail full of stairs at high altitude and our poor, out of shape bodies were not worthy. The entire hike felt like days and days of stairs. Mike took the lack of oxygen particularly hard and at one point would climb a couple stairs, sit down and take a break, climb another couple stairs, sit down and take a break. After a day of this, Mike wanted to hire another porter to carry the rest of our stuff so that all we would do is carry our bodies up the stairs – but given the fact that porters were already carrying our food and tents, I thought that was wimping out. He wheezed up the stairs, dehydrated and suffering from diarrhea (a side effect from altitude sickness medication), pissed at me the whole day. Even now, if someone asks how the trip went, he just says “hire the porter.”

The safety and preparedness the guided hike provided (vs the Grand Canyon) came with not being able to go at our own pace, of not being able to feel like we “discovered” anything or properly, slowly, explored some place. Instead we were constantly trying to keep up with and almost race other people – it was a good day when we weren’t “last.” Between moments of truly basking in the landscape, we were racing to not be left behind. People were so focused on “finishing” when the whole point of hiking to Machu Picchu is the journey.

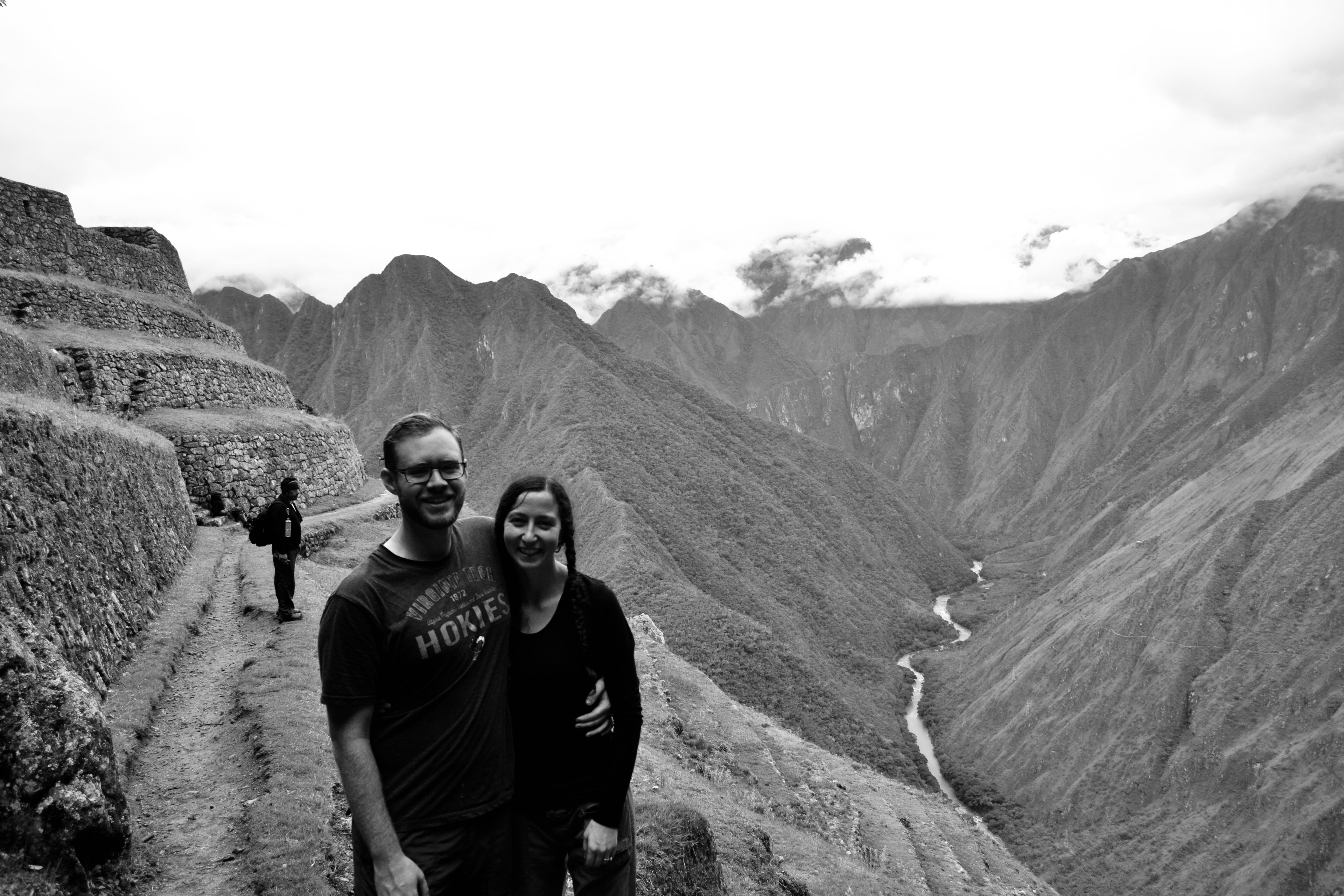

One of the best moments of the entire trip was sitting on the edge of the stone ruins of a terraced mountain, looking out over the valley with the Urubamba river snaking its way through mountains that were treated as gods. It was peaceful. A shepherd herded his llamas through the grassy terrace and Mike dreamed of telecommuting to work and never leaving this very spot. I think that made it all worth it – taking the slow journey, a pilgrimage to Machu Picchu instead of just a train ride. Although I should continue to work on not almost killing us so much, I do have this philosophy that the slow, sometimes painful route makes these moments all the sweeter. You feel more alive having conquered your self-doubts.

As a final note, I have been advised that we are not allowed to go hiking for our honeymoon – apparently a honeymoon is supposed to be fun and relaxing for some reason. I’ll see about that.